A System of Technical Debt

In this article we introduce an eight state system of technical debt, and analyze it’s behavior.

What is it?

According to an article by Frank Buschman, the term “Technical Debt” was coined by Ward Cunningham and is defined as:

…a metaphor for the trade-off between writing clean code at higher cost and delayed delivery, and writing messy code cheap and fast at the cost of higher maintenance efforts once it’s shipped.

While that is an excellent definition, it isn’t always obvious and dramatic. Even mindful, vigilant teams who follow agile practices including peer reviews, continuous integration, and a thoughtful definition of done (DoD), still find themselves accruing tech debt.

Tech Debt comes in many forms, including but not limited to insufficient test coverage, code quality problems, inadequate documentation, out-of-date dependencies, and failure of code to meet project standards. Examples of code quality problems might typically include messy code, duplication, unnecessary complexity and the oft tempting re-invention of the wheel.

Why does this happen?

If you review the wikipedia entry on this topic, you might notice that many items listed as causes of tech debt appeared to actually be examples of tech debt. This is confusing until it becomes clear that…

Technical Debt has a Feedback Loop

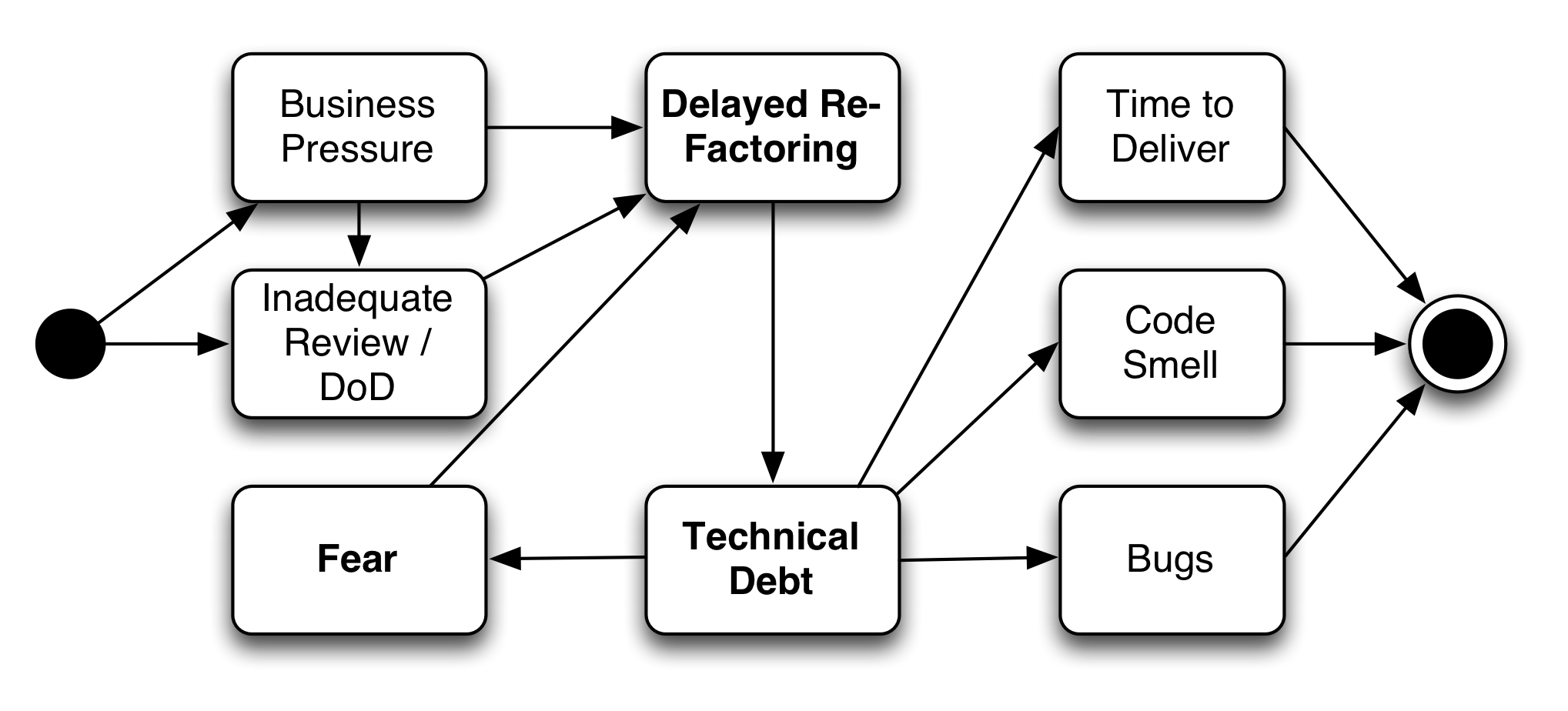

Technical debt actually begets more tech debt over time, and it deserves it’s own state diagram:

Let’s walk through different states of tech debt and attempt to understand the flow.

Business Pressure

Sometimes we can hear our product owners channeling Larry the Cable Guy, drawling “Git-R-Done!”. Customers care about business value, delivered in a timely fashion, according to the budget. They are often less interested in the details of code coverage, code quality metrics, multiple peer reviews or whether or not we’re several versions behind the latest version of [insert your favorite framework here].

This business pressure can cause a team to compromise review and/or standards established by it’s definition of done.

Inadequate Review / DoD

Inadequate review can be caused by business pressure or an inadequate definition of done.

Delivered code may deviate from the technical design, contain wheel re-inventions, include duplications or may be incomplete in terms of done. For example, the code might include unit test coverage and still be missing integration tests.

When the definition of done is missing or inadequate, different standards may be applied when a task is completed. (The DoD helps alleviate this by providing a checklist for authors and reviewers who can then practice adequate peer reviews against a standard.)

Delayed Refactoring

Business pressure and inadequate review lead to delayed refactoring.

The art of writing computer code is a process of continual restructuring and iterative rework. At some point we must accept a level of completeness in order to deliver the solution. At that time, there could still be more work that needs to be tackled… refactoring is delayed. We may be aware of this delayed refactoring situation at the time when a decision is made, or we might not be aware of it.

While delaying things now results in short-term gains, the long-term implications of not performing them (code coverage as a glaring example) leads to tech debt.

Technical Debt

Delayed refactoring leads to tech debt.

The decision or non-decision to delay refactoring means we now have tech debt. Often, we have incurred a future cost in the system that will be more painful to pay off down the road then if it had been addressed right now. This tech debt could be in the form of:

- insufficient test coverage

- code quality problems

- inadequate documentation

- out-of-date dependencies

- failure of code to meet project standards

Fear

Tech debt leads to fear.

You are on Degobah and your ship just sank to the bottom of a bog. it’s stinky, dark and foggy. Something large and silent just slithered a few feet from where you stand on an unbalanced tangle of tree roots. A voice seemingly from nowhere (which sounds oddly like Miss Piggy with throat congestion) asserts “Technical debt leads to fear, fear leads to delayed refactoring, delayed refactoring leads to technical debt, technical debt leads to”… we are now caught inside the feedback loop of Technical Debt, Delayed Refactoring and Fear.

Scenario - insufficient test coverage:

Alice: "I really want to refactor this code, I need to use it but it's smelly and I think there might be a bug in one of the bounds conditions"

Bob: "If you refactor that, what else is going to break?"

Alice: "I don't know."

Bob: "Don't touch it, make a copy"

Congratulations, we just created more technical debt. The only way out? You guessed it - “Suffering”.

Time to Deliver

Tech debt eventually demands to be paid off, which increases time to deliver.

Ironically, by compromising in the immediate interest of time we have actually made it more difficult, and therefore longer to deliver a future feature because at best we will need to meet the definition of done and perform the refactoring that was delayed just now. In the worst case, as more technical debt piles up, time to deliver will continue to increase until eventually managers and customers will wonder why we can’t seem to get anything done on time.

Code Smell

As compromises are made in the interest of delayed refactoring, code quality suffers and developers may also start to notice strange patterns or smells developing in the codebase. These smells are a flag that something needs to be refactored. They can also lead to future bugs and increased time to deliver, as co-workers struggle to decipher what the code actually does.

Bugs

If your team cuts corners on unit or integration test coverage, it risks delivering code that hasn’t been exercised, especially at the bounds. That means you don’t really know (and cannot prove) if it works or not, and it’s likely to have bugs.

Another less obvious path to bugs happens when dependent library upgrades are neglected. For example, if our dependencies fall out of date, we may miss a security fix. If we are eight versions behind the current stable, supported version and code coverage is low, an upgrade cannot be performed without incurring significant new, unplanned cost in terms of time and effort in addition to dollars.

End States

When not placed in check, these last three end states represent suffering and pain in our system. In the worst case this results in an unmaintainable product, and destroyed business value. Hopefully the importance of adequate review and high standards for definition of done are becoming clear. The feedback loop in the system makes it imperative that tech debt is tackled iteratively to prevent it from snowballing. In the next article we explore agile practices and strategies for dealing with tech debt.

blog comments powered by Disqus